Neil Woods is an extraordinary person. He spent fourteen years living a double life, inhabiting the skin of a heroin and crack cocaine addict whist working as an undercover police officer. Now he’s the chairperson of LEAP UK, and a prominent campaigner for drug policy reform. Sensi Seeds interviewed him about cannabis legalisation and the war on drugs.

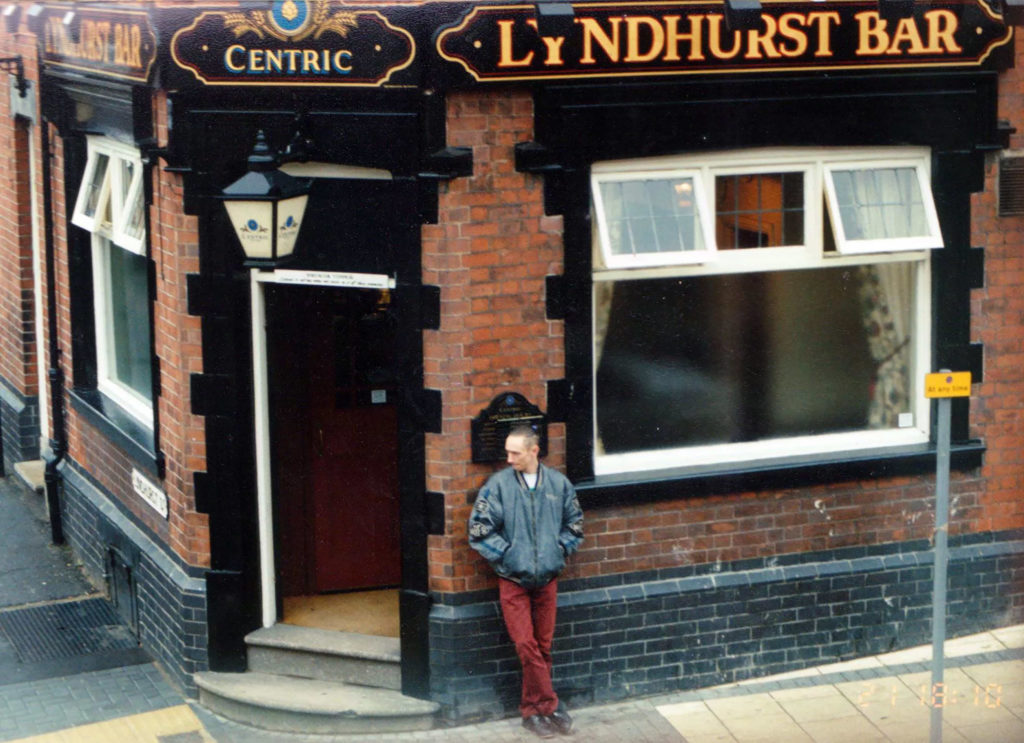

I first met Neil Woods at the Product Earth Expo in Birmingham, UK, in 2017, where he was promoting the UK branch of Law Enforcement Action Partnership (formerly Law Enforcement Against Prohibition) and his book, ‘Good Cop, Bad War’. Neil was in a booth next to the United Patients Alliance, where the vaporizers were in full effect. He didn’t even seem to notice this clandestine disregard for the law he had once sworn to uphold.

Later, Neil gave a talk on the futility of the war on drugs and the damage it is causing, and cheerfully answered questions about how to spot undercover police in grow shops (they seem really friendly, ask a lot of questions and want to meet your mates). When he asked if Sensi Seeds wanted to cover the launch of LEAP Scandinavia at the Nordic Reform Conference in Oslo, and maybe interview him, the answer was a definite yes.

Good Cop Bad War – a darkly fascinating book

This is by no means the first interview that Neil Woods has given. Since the publication of his autobiographical polemic ‘Good Cop Bad War’ in 2016, everyone from the Guardian to Penguin Books have asked him about the time he spent as an undercover Drugs Squad officer. It’s a genuinely gripping, darkly fascinating book. To someone who has always been on the other side of the war on drugs, it reads as a vindication, but also a cautionary tale to trust no-one in authority, especially if you are working for them (almost like Orwell’s ‘1984’).

Neil Woods had increasingly serious doubts about what he was doing: targeting the most vulnerable people in society, who became collateral damage once they had given him the information he needed to get further up the chain of drug dealers; and, how he was doing it.

The police teams that were supposed to be backing him were rife with infighting and corruption, psychological support was virtually non-existent, and even the equipment he was issued was dangerously outdated (Neil was very nearly killed when a gangster spotted a bulky hidden camera in his jacket; he discovered later that a tiny state of the art version was being held in reserve by his superiors for ‘Level One’ operatives – those who spied upon richer but less personally violent criminals).

Smoking cannabis before joining the police…

Nevertheless, it took well over a decade for him to conclude that drugs should be legalised. In the case of cannabis, for most of our readership, that conclusion is reached simply by using it. In fact, Neil Woods had repeatedly smoked cannabis with enjoyment before he’d joined the police force.

“A friend of mine told me that smoking hash was amazing for listening to records, so we would occasionally score a bit of dope off someone’s older brother, then lie back and listen to The Doors and Yes. As promised, it was pretty amazing”, he relates in the book, soon followed by the admission that he never got into Ecstasy, but “A few tokes on a spliff and I could dance all night at the Haçienda with everyone else”.

…and smoking cannabis after joining the police

Sometimes, consuming cannabis was vital to maintain his cover: “To skip my turn on the bong would have immediately exposed me as a narc … So, I took my turn. And I got absurdly high… No one on the Drugs Squad ever actually asked why I was giggling maniacally while filling out my evidence book, but I think they could have hazarded a guess”.

Sometimes, such as at a free party notably lacking in gangsters, it was purely for fun: “I went and got some nice Thai stick and Moroccan resin, and Cate rolled a big hash-on-grass spliff. Then we danced our arses off to Detroit-influenced soulful techno…” By this point in ‘Good Cop, Bad War’, rather than being annoyed by any perceived hypocrisy or use of taxpayers’ money to get police officers high, I was actually relieved that he got to have a brief respite from the stress and danger of the rest of his job.

The interview

So, having delved a little into Neil Woods’ background, I sat down with him at the Nordic Reform Conference and asked him about cannabis, prohibition, law reform, and what he’s told his own children about drugs.

Q1 Why does cannabis need to be legalised?

Neil: The need to regulate cannabis is a child protection issue. We need to protect children from cannabis in much the same way that we protect them from alcohol. In the UK, less than 1% of teenagers can buy alcohol from a licensed premises; over 50% have easy access to cannabis. We should not be allowing that to continue.

But it’s not just protection from the drug that’s the important thing. The gangsters of tomorrow come from the young people who are corrupted into that lifestyle, and organised crime recruits those young people through the teenage cannabis market. They lay half an ounce [14 grams – ed.] on a teenager, a 14 year old, and say “Come back when you’ve sold 14 one gram deals”. That 14 year old has the kudos of having the best weed. They have spending money. And they suddenly have the attention of people older than them, who bring them into their team.

Prohibition causes increased aggression in teenagers

This happens all over the place. The trouble is, the most successful of those teenagers are recruited to transport heroin and crack cocaine in between major cities and smaller towns, as laid out by the National Crime Agency. Because they’re successful at that, some of them get recruited into actually street dealing those products. And in so doing, they have to adopt the team ethos. But what that means is that the teenagers who go into that are having their personalities changed.

They have to become more aggressive in order to protect the team from being grassed up. The police pay money to informants, so you’ve got to terrify people to balance that payment offer. The most successful teams are the ones who can scare people into not informing on them.

Cannabis legalisation is a child protection issue

At LEAP UK we would advocate the legalisation of all drugs, but we know that the government are very far away from doing that. However, the government are closer to regulating cannabis. Regulating cannabis would create an enormous buffer between organised crime and our young people. It would genuinely improve the situation and undermine the power of organised crime.

So we have to make that clear to people: this is not about arguing the harms, this is not about arguing that cannabis is safe, and that people have got it wrong. That’s not the way to win people’s minds. It’s not about arguing that it’s good for people’s health and that’s why we need to legalise it. In some cases, that might be true, but that’s not how to win the argument. The way to win this argument is to make the point that this is a child protection issue.

Q2 How did the conversations about cannabis go with your kids? Did you talk about it with them from a young age?

Neil: My son is 18 on Sunday, and my daughter is 20. Yeah, I told my kids about all drugs from a young age. Everything from the history of the opium wars, all the way through to the racism in drug policy; I’ve given them the lot.

I’ve told them that cannabis for young minds isn’t so good; for developing minds it shouldn’t be done, and it certainly shouldn’t be done excessively or too often for minds under 18. I’ve told them I’d rather they didn’t do anything ‘til they’re 18, but I’ve also told them, for example, the estimated doses for MDMA. I’ve told them the increased risk to young people for having too large a dose of MDMA, and that the ideal starting dose is 80mg, and all of the different harm reduction aspects of any kind of drug taking.

So while saying that I’d rather they didn’t, I have also told them to the best of my knowledge – and I am a bit of a geek – to the best of my knowledge, the safest way to do anything if they did decide to try it.

Harm reduction advice

They are safer for that knowledge, in whatever decision they make. That is the key thing. With cannabis in particular, in the UK – and I think it’s much the same around Europe – 80% of people can only get high THC cannabis with very little CBD. And that’s no good for a young mind. An adult can make those decisions; I would be less concerned about adults using high THC products than kids.

So my harm reduction advice to them was, I’d really rather you didn’t, but if there ever is a choice, then oldschool 1:1 Moroccan hash is better than really stinky high THC weed.

Q3 What do you think about the Netherlands model of splitting cannabis from hard drugs?

N: When it happened in 1976, when the health minister separated cannabis from heroin, it was to try and decrease the amount of contact people had with the heroin market, and it worked. The evidence clearly shows that the Netherlands didn’t have the same problem in the 1980s heroin explosion as the rest of Europe did; and that it was a very forward-thinking decision.

It was a brilliant policy stroke at a time when it was very difficult to make those kind of policy decisions, and it was a fantastic idea. Times have changed, and more radical solutions are needed now, but I would hope that the Netherlands comes up with some innovation that follows that tradition of innovation.

Q4 Could we simply announce that the war on drugs has been won, and move on?

N: Well, I think that that would be really tricky… In order to win this, we have to reframe it, and to say that we’ve won is not reframing it, it’s utilising the language that’s in existence already. To me, that plays into the traditional view, the United Nations declaring that we can achieve a drug-free world. The terms of victory are only within those terms. So I would rather say that we will win by surrendering, and take a more passive stance. Take the heat out of the idea of fighting it as a war.

It’s complicated, because you have to convince different audiences in different ways. So you have to fight this – again, I’m using a battle analogy, aren’t I? – you have to fight this on different fronts, and in different ways. You’ve got to speak to politicians, but the politicians aren’t going to change their minds unless you convince them that there’s votes in it. I’m not being cynical about the nature of politicians, that’s democracy.

Growing a social movement for drug legalisation

It’s about growing a social movement. You grow a social movement in all kinds of different ways, and that’s where LEAP UK, and LEAP across Europe and across the world, comes in and can help. People listen to police because we’ve been on the front line. So I think there’s a channel there. We need to get the funding, we need to get the media contacts, and just work on growing the social movement. And if, for some audiences, part of that message is “we’ve won and let’s move forward”, then so be it. I would listen to any strategic thoughts on the best way of getting the message out.

Q5: Being in LEAP is obviously very different to being in the police, but is the any similarity? Is there a similar sense of community?

N: Well, I never had any sense of community in the work I used to do, because I was separated even from my own ranks. I couldn’t tell any of my colleagues who weren’t involved, and the people I worked for, well, when I was dropped into an undercover op, I was using a pseudonym to the cops I was working with. Even they weren’t allowed to know my real name, and they could be disciplined for asking me. They were told that on the first day of the job. Obviously, it was a protection against corruption.

“Former undercover cops are the most enthusiastic”

It’s liberating to be able to talk honestly. I’m having a fascinating sense of community from the police that join us all the time. There’s two particular new ex undercover cops who have joined us this year who are wonderful. They’ve been there, and they understand, and they’ve come to some of the same conclusions. The sense of community’s been great.

It’s interesting that former undercover cops are the most enthusiastic, because we’ve seen – and caused – harm right on the ground; right on the front line. So it’s interesting mixing with them. So yeah, suddenly I have a sense of community. To be honest, just to able to be honest is good.

Neil Woods, thank you very much for this interview

‘Good Cop Bad War’ has also been optioned as a TV series. Neil is working on the sequel, ‘Drug Wars’, with the same co-author, JS Rafaeli. Publication is expected in June 2018. LEAP UK can be contacted via their website, Twitter, and Facebook, and you can also follow Neil on Twitter and Facebook.

As always, Sensi Seeds will continue to report from all fronts of the war on drugs; let us know what you think in the comments below.

Darryl and Scarlet,

I thought I’d briefly answer the points here. Firstly, Darryl and I, and many of the drug law reform community have disagreed over the semantics. I do however agree with much of what Darryl says, for example I agree that freedom of self should be absolute, and that drug laws are drug prejudice. They are control over behaviour. I understand Darryl is a good lawyer, and I’m certain I couldn’t possibly conduct myself in the language heavy arena of the court as well as he. Unfortunately for the pursuit of an evidence based policy, the general public don’t follow the rules or discursive parameters of a court room. Established preconceptions require tactical approaches. I suspect Darryl would have fared no better as an undercover cop than I would as a lawyer. I do understand that I lose the ethical high ground by saying that.

The reason I wanted to reply though is to say that Darryl is correct. In 2015 the most terrible draconian law came into effect in the U.K. Cannabis consumers are now persecuted through driving. The premise that impairment is the judge if fitness to drive has been removed. Trace amounts of cannabis in the blood is enough for a ban. If the driver has such drugs as diazepam in their system they can have a defence is it is prescribed. For cannabis there can be no such defence. This law was brought in for political reasons, and is a drug apartheid. It is used to persecute minorities, as it affects the livelihood of those affected.

I had to respond to support that point that Darryl made. Whilst I stand by the comments that police are driving reform in terms of liberisation, I agree that the collective oppression of minorities in this way is an horrendous situation.

Hi Neil,

Thanks for your reply, and for answering the points raised. I agree that the change in law to no longer look at impairment in the case of cannabis use is dreadful, and only results in more suffering. I don’t think I gave adequate context for my question – Darryl mentions ‘drugs’ rather than cannabis specifically, and to claim that *no* drugs impair one’s ability to drive is quite a statement. Additionally, having more solid research to back up the lack of impairment cannabis causes is always good.

With best wishes,

Scarlet

Its a very poor level of understanding. Intervewer and interviewee are both Stuck in the prohibitionist mindset where objects presume legal status. There is no legality in cannabis or in any substance, legality only applies to human actions. Once this is understood the whole regulatory apparatus from the misuse of drugs act can be appreciated. This falls Paradyne where drugs can be legalised means that we exist within a binary understanding of the problem Rather than appreciating that we have legal agency and that we can be regulated proportionately to address the potential social harmfulness of the misuse of any substance.

There is no evidence of the government legalising cannabis as Neil describes it incorrectly, and it is a great shame that a law enforcement organisation and police officers cannot state the law correctly rather use these linguistic shortcuts which actually assist the probation mandate through deception. The first thing to realise is that drugs cannot be legal or illegal and these terms refer to your actions. There is a huge distinction between stating the law correctly and this is sloppy terminology which has come into common parlance just been adopted by almost everybody. It is the miss use of language which prevents any meaningful progress. Anyone who thinks that the law is getting better in this country regarding the peaceful use of drugs is misguided. We now have a situation of zero tolerance for many drugs with driving Despite there being no correlation with impairment, we have widespread drug testing despite there being no correlation with impairment, creeping out across the workplace and it will extend to many other walks of life soon.

Hi Darryl,

Thanks for commenting. Unless I misunderstand your comment, you initially seem to be arguing a semantic point. Although it’s an interesting philosophical view, in practical terms, in most countries the end result is the same if one gets caught with cannabis whether one views the cannabis itself, or one’s possession of it, to be illegal.

You write “Anyone who thinks that the law is getting better in this country regarding the peaceful use of drugs is misguided.” If by “this country” you mean England, it may interest you to learn that arrests for possession of cannabis in England and Wales have dropped by 46 percent since 2010, cautions dropped by 48 percent and charges fell by 33 percent (figures from from police forces released under the Freedom of Information Act in 2016). Despite this, data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales shows that cannabis use has remained consistent between 2010 and 2015.

I am interested to see where you are getting the data to back up your statement that there is no correlation with impairment if using drugs whilst driving. Please can you provide a link to your source(s)?

With best wishes,

Scarlet