Although much of our early history of hemp use has been lost in the mists of time, we still find odd echoes of it every now and then – in old medical texts, in archaeological digs, or even in a folk song or poem that has survived the passage of time to remain essentially intact. Here, we take a look at some of history’s finest and best-preserved examples!

In many cases, these poems and songs are evidence of just how important hemp was to our ancestors. But even more than that, they give us a direct view into historic usage and socio-religious attitudes towards hemp, which can help us build up a much richer idea of the past! Let’s take a look at a few examples.

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1595) – William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare, the great English playwright of the Elizabethan era, made several references to hemp in his works. Interestingly, most of the references he makes have somewhat negative connotations. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“What hempen homespuns have we swaggering here,

So near the cradle of the fairy queen?”

Here, “hempen homespuns” implies crude, rural people unfit to be in the presence of the queen. Then in Henry V, hemp’s association with the hangman’s noose is emphasised:

“Let gallows gape for dog, let man go free,

And let not hemp his windpipe suffocate.”

In Henry IV, Pt 2, this association is made again when Mistress Quickly refers to Falstaff as a “hempseed” – in Elizabethan slang, this apparently meant a person destined for the gallows! In fact, another contemporary saying was “the hemp is growing for you” – meaning that the person addressed risked death by hanging if they continued their current behaviour.

Interestingly, there is also archaeological evidence suggesting that Shakespeare himself actually smoked cannabis (although its accuracy is disputed). In 2001, several smoking pipes containing ancient traces of burnt compounds were found in Shakespeare’s Stratford-Upon-Avon property. Tests showed that cocaine and nicotine were certainly present, but the evidence for cannabinoid residue was less clear-cut.

If the Bard was a lover of cannabis, he certainly was much more discreet than the next poet on the list…

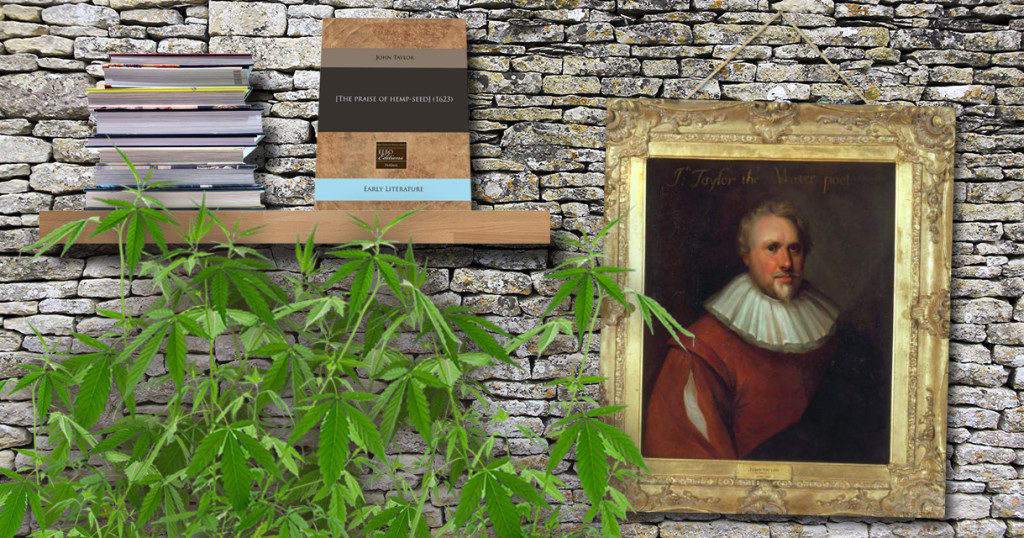

“The Praise of Hemp-Seed” (1620) – John Taylor

This 17th-century English poet was a contemporary and possibly a close of friend of William Shakespeare, and this particular poem is actually notable for containing one of the first known published mentions of Shakespeare’s death. It even goes into detail about how poets such as Shakespeare literally depended on hemp to exercise their art, as it was the primary source of fibre for paper at the time.

Here’s the section that talks about Shakespeare:

“In Paper, many a Poet now survives

Or else their lines had perish’d with their lives.

…

Spencer, and Shakespeare did in Art excell,

Sir Edward Dyer, Greene, Nash, Daniel,

…

Forgetfulnesse their workes would over run,

But that in Paper they immortally

Doe live in spight of Death, and cannot dye.”

Indeed, this epic poem is so unabashed and ardent in its expression of love for the hemp plant that it rivals any modern-day activism in its passion and resonance. It’s definitely a far cry from Shakespeare’s reticence – yet even here, it remains ambiguous as to whether cannabis was used for recreation as well as industry. The poet points out that hemp can bring “pleasure”; but also that:

“Apothecaries were not worth a pin,

If Hempseed did not bring their commings in;

…

Elixirs, simples, compounds, distillations,

Gums in abundance, brought from foraigne nations.”

Here, Taylor is pointing out that ships built from hemp allowed trade and import of exotic foreign goods such as medicines. One would think that if cannabis tinctures, hashish and so on were already being imported as part of this vast pharmacopeia, the poet would relish the irony and would make the point in an obvious way!

“The Hemp – A Virginia Legend” (1916) – Stephen Vincent Benét

This early 20th century poem is presented as a retelling of a folk legend, but may be entirely a product of the author’s imagination. According to the poem, a pirate (“Captain Hawke”) violates and kills the daughter of a powerful landowner (“Sir Henry”), who then embarks on a long, drawn-out plan to take revenge. The poem revolves around the motif repeated by the pirate – “the hemp that shall hang me is not grown” – as he continues his campaign of rape and pillage.

What follows is a lengthy description of the sowing, growing and harvesting of a “voodoo” crop of hemp in a Virginia plantation. A notable snippet:

“And where the furrows rent the ground,

He sowed the seed of hemp around.

And the blacks shrink back and are sore afraid

At the furrows five that rib the glade,

And the voodoo work of the master’s spade.”

Our “hero” (who is, let’s not forget, probably a slave-owner) eventually confronts the pirate and kills him with a specially-prepared hemp rope. The poem concludes:

“But down by the marsh where the fever breeds,

Only the water chuckles and pleads;

For the hemp clings fast to a dead man’s throat,

And blind Fate gathers back her seeds.”

As we see, this entire poem ties in very closely with the Elizabethan idea that “the hemp is growing for you” – and beyond the simple association with the hangman’s rope, here the connection between hemp and death seems abstract, occult, and somewhat otherworldly.

“Song of the Orphan” – Traditional, Ukraine

“…And

what is that to me, if I am still young, if

I am still an orphan?

As the soaking hemp rots in the water, so lives

an orphan in this world.”

This plaintive song from pre-20th century Ukraine, collected by the great Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, compares life as an orphan to hemp slowly rotting in a stagnant pool. This may seem bleak – but the end result of the process yields fine, strong fibre, so perhaps the message contained here is more positive than it appears at first.

Interestingly, Ukrainian peasant girls traditionally performed a love spell in which they “pretend to sow hemp-seeds and forecast whom each of them is going to marry”. This spell is remarkably similar to that described in Robert Burns’ Halloween. The Ukrainian version wasn’t performed on Halloween but on the 30th November – the day of St Andrew, who also happens to be patron saint of Scotland!

The extent of shared ritual and folklore in Europe throughout history is intriguing – take a look at R.C. Clarke’s excellent work Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany for more detail on hemp traditions.

“Halloween” (1785) – Robert Burns

Robert Burns, the National Poet of Scotland, has been forever immortalised in folk history for his world-famous contributions such as “Auld Lang Syne”. However, a look at one of his more obscure poems yields some surprising contemporary detail about how hemp was used.

In the poem “Halloween” (1785), Burns hilariously describes the folk charms, rituals and games played by a group of young, rural field workers in 18th century Scotland one Halloween night. Amazingly, hemp seed features prominently in a traditional love-spell he describes:

“Hemp-seed I saw thee,

An’ her that is to be my lass

Come after me, an’ draw thee

As fast this night.”

“Hemp-seed, I sow you,

And she that is to be my woman,

Follow me, and reap the hemp,

As fast as I sow.”

Unfortunately, the skeptical young man that attempts the ritual is coincidentally followed by a local pig from the village. In his suggestible, drunken state, he mistakes the pig for a local, elderly woman, and believes that his efforts have resulted in something quite different than hoped for! Here’s an excellent rendition of the poem performed at a Halloween event in Scotland.

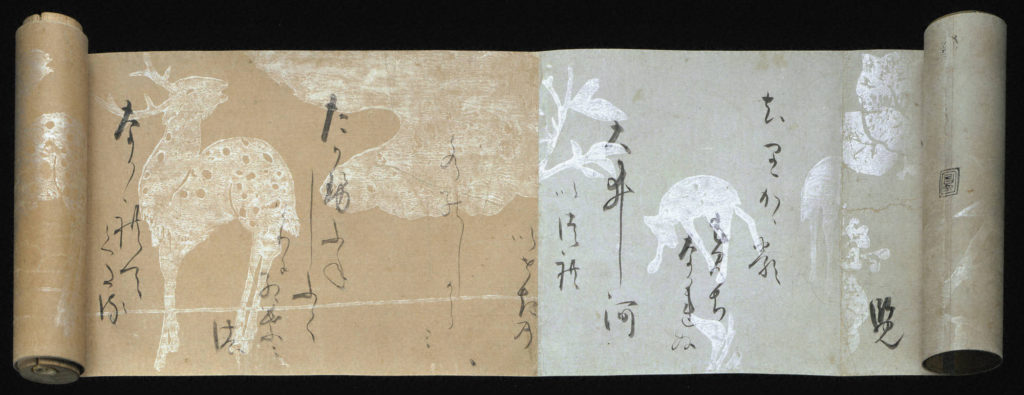

“A Lament on the Evanescence of Life” (660–733) – Yamanoue no Okura, Japan

Japan is a country with a long history of hemp use, and a rich tradition of poetry. Japanese poetry can be highly metaphorical, and interpreting the intended meaning is the subject of esteemed intellectual debate. Here’s a section from the poem mentioned above, which as the name implies, is a wistful consideration of the brevity of life and the imminence of old age and death:

“who, as fine young men will do…

placed on red horses

saddles fashioned of striped hemp,

climbed onto their steeds,

and rode gaily here and there?”

In another poem believed to have been written some years later, Dialogue Between Poverty and Destitution, the poet laments: “But I’m cold all the same. I pull over me/My bedding of coarse hemp”. A sense of gentle existential despair pervades these and many other Japanese hemp poems. In the 13th century, poet Fujiwara no Tekei would write:

“When we parted

dewdrops fell down on my sleeves

of pure white hemp–

your coldness harsh as the hue

of the piercing autumn wind”

Again, we find associations with sadness, loss, fundamental change – the joy and warmth of summer shattered by the piercing cold of autumn, and love replaced by loneliness. Hemp, as an annual plant that died and was born again each year, has surely aided many a thinker over the millennia in their musings on life and death, bounty and deprivation, love and loss. Harvest time, with its obvious bounty and joy, is also the harbinger of the cold death of winter.

Another association that crops up repeatedly in the Japanese tradition is between hemp and “purity”, often with emphasis on the whitish colour of the undyed cloth.

Also in the 13th century, the military leader H?j? Yasutoki penned the intriguing lines, “In this world no traces of hemp are left; Only mugworts grow as they please”. Here, “mugworts” refers to untrustworthy schemers, while “hemp” refers to honest, morally ”pure” individuals. Of course, history being as cyclical as it is, these words could be a very apt descriptor of our present situation.

From these diverse examples, we can surmise that hemp has meant many things to many people over the millennia that have passed since we first encountered it – and that although its many uses may have traditionally been utilitarian, its importance often went far beyond the prosaic. Now, as diverse cultures and traditions throughout the world are being destroyed one by one, it’s of fundamental importance to preserve the records of the past in as many ways as possible.

If you know of a traditional hemp folk song or poem from your country, let us know in the comments!