The dealings of the world’s current hash market often leaves cannabis farmers in developing countries exploited. Cultivators and processors receive a tiny fraction of profits made from the industry. Is there any way of developing Fair Trade hashish, or is it a pipe dream for the future, if widespread legalization ever takes place?

What if there were a worldwide fair trade system for the production and sale of hashish and marijuana?

For centuries, Afghan and Indian farmers have grown cannabis crops in order to produce hash. For some villages in these two countries, it is the primary source of income. Farmers can be paid anywhere between €70 and €180, while the consumer can pay up to €14,000.

Over 90% of the money circulating the hash trade ends up in the hands of the hundreds of middle-men that transport hash from the farms of Afghanistan and India to consumers, clandestine drug dealers and coffeeshops or social clubs around the world.

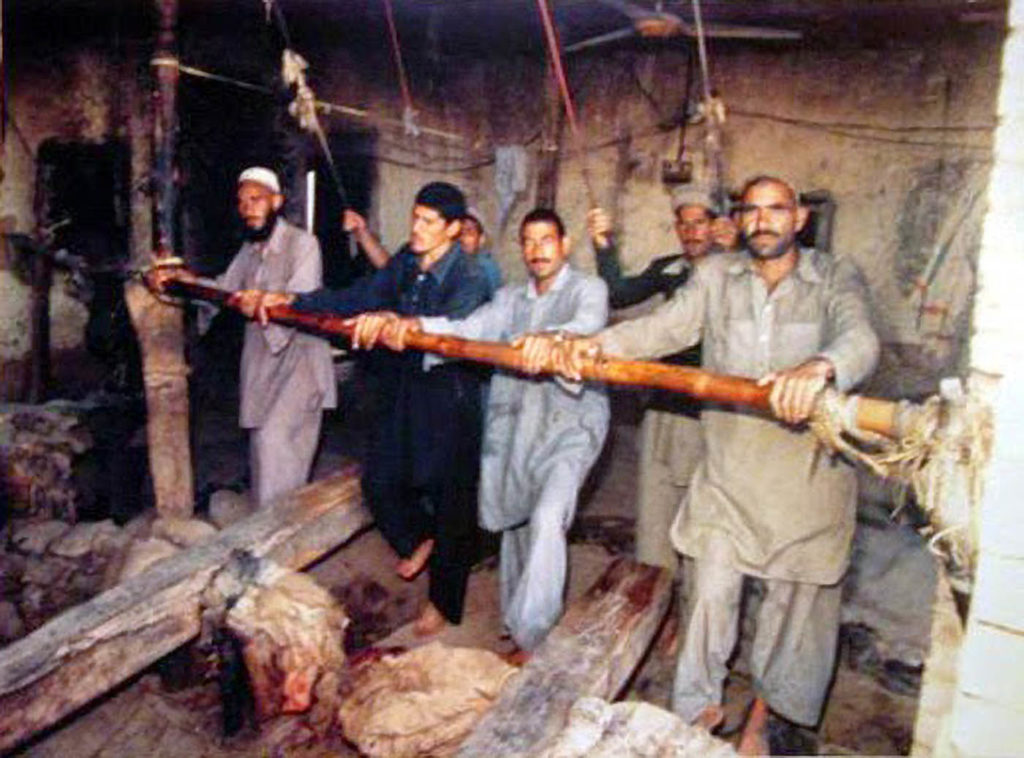

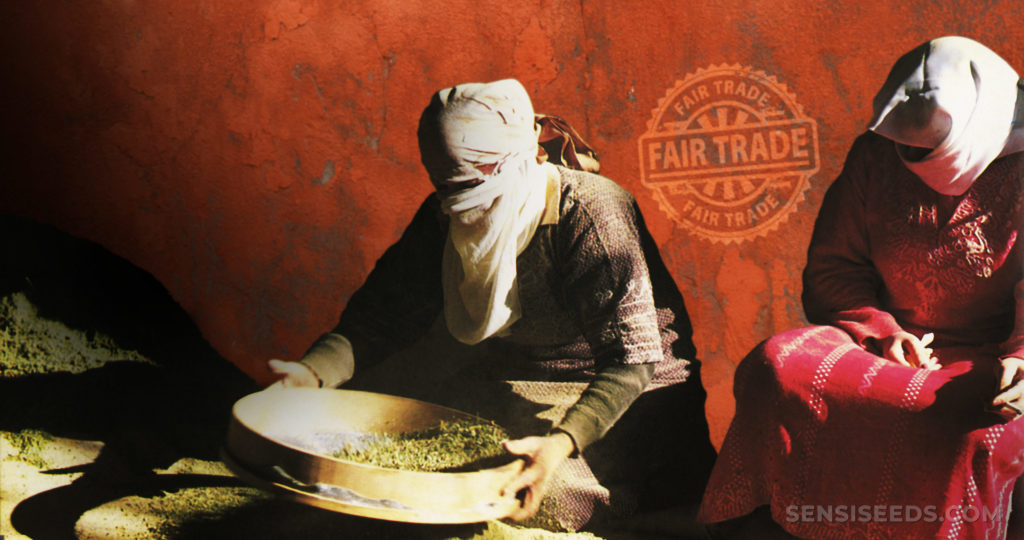

Farmers, their families and other low-paid agricultural workers perform the entire job of producing hashish – cultivating the cannabis crop throughout the growing season, harvesting and drying the mature plants and collecting their resin.

The job of pressing the raw resin into hash is sometimes done by the farmer, sometimes by local collectives. At this point, the hash is ready for consumption, yet the vast majority of the final price goes to the organisations that simply transport the hash to its final point of sale.

It’s a side-effect of the illegal drug market that farmers around the world are coerced into growing highly valuable, illegal crops, even at the expense of growing food for themselves and their families. The majority of cannabis grown in the East (India and Afghanistan) is done so illegally, and much of it is transported to Europe or the USA where it can be sold legally and for a higher price. This is how Moroccan hash or Malana cream makes it into Amsterdam coffeeshops.

In the absence of an internationally recognised, legal hash market, exploitation of cannabis farmers in Afghanistan and Morocco is commonplace. This is because farmers in developing countries are keen to grow high value crops to supplement their income. Often, these high value crops are illegal ones such as opium and coca. The majority of wealth created by these crops ends up in the hands of local warlords, organised criminals and even corrupted politicians.

To give an example, in one UN report from 2010, the net income per hectare of cannabis in Afghanistan was estimated to be somewhere around $3,300, about €2970. The UN also estimated in the same report that about 145 kg of cannabis resin (hash) could be extracted per hectare. In 2007, one kilo of hashish in The Netherlands had a market value of around €1900. Now, for the 145 kg of hashish that can be produced per hectare in Afghanistan, there is a gross value of over €275,000 in The Netherlands. It’s a grand total of 1% of the total revenue in the hands of the farmers.

Herbal cannabis does not face as dramatic an issue of trade on an international level, as it’s not often transported internationally. Therefore, in most countries, cannabis is grown locally. Needless to say, there are still concerns about employee rights and wages in legal countries. For example, in the USA, there has been major concern over the employment rights and working conditions of trimmers, and even issues with travellers working illegally on cannabis farms.

A fair price for hash would allow farmers to generate a liveable income by growing cannabis on a small part of their land, while still producing food for themselves and their communities from the rest. This is perhaps somewhat idealist, as in order for a truly fair trade to exist, the entire operation cannot run illegally. It could be argued that one of the biggest contributors to the unfair dealings is precisely the fact that transportation of hash around the world is illegal and risky.

How the existing hash market is set up

Most of the world’s hashish comes from Afghanistan, Morocco and India. The price varies between places, and it is speculated that hash prices are the highest in Morocco. As mentioned, farmers can receive as little as €70 – €180 per kilo in Afghanistan, but as much as €1500 per kilo in Morocco.

Proximity to the European market plays a great role here, as Morocco is a short boat ride from southern Spain. In comparison, Afghanistan is almost 5,000 km from Europe, and the cost of getting the product to the end market is therefore much higher. India, on the other hand, is up to 6,000 km away from Europe, and the cost and risks associated with international transport are higher again. This obviously plays a role in how much buyers are willing to spend at the original source of hash.

Why is a fairer system needed?

It is primarily the large scale Moroccan farmers that can afford to set up grow operations capable of sustaining modern types of cultivation. The traditional farmers though, who are still the majority, receive low compensation for their products, and live in poverty with limited rights.

Afghani hash is typically seen as being of lesser quality than Moroccan, and thus it generally commands lower prices all the way along the supply chain from producer to retailer. In general, Moroccan hash direct from the supplier ranges from €250 to €1500 in price per kilogram, while Afghan hash, as stated, costs approximately €70 to €180.

A kilogram of Afghani hash at maximum wholesale value ranges from €750 to €2500 in Amsterdam, while a kilogram of Moroccan hash ranges from something closer to €1000 for lower qualities and up to €6000 for the highest grades. And in the coffeeshops, at retail prices, Afghan ranges from €2.50 to around €10 per gram, while Moroccan fetches something more like €4 to €16 per gram.

Afghan average salaries are also generally considerably lower than Moroccan. In Afghanistan, the median annual salary is approximately €8000 per year, while in Morocco the figure is closer to €20,000. These factors must be kept in mind when considering what constitutes a fair or unfair salary in each country.

However, the vast majority of the profits generated in both markets are nonetheless claimed by the criminal organizations that transport the hashish to Europe. This shouldn’t be seen entirely as the fault of those who participate in the transportation of hash. After all, the law is an overwhelming factor that creates this kind of environment, as transporters are at a great risk of imprisonment, and therefore demand a high price.

Thus, there is certainly a case for amending international law, regulating the market and enforcing fairer business practices among exporters and importers.

Is there any such thing as fair-trade hashish right now?

In a word, no. For something to be Fair Trade in the legal sense of the word, it has to be certified and approved by The Fairtrade Foundation and its certification body, FLOCERT. Obviously, this cannot happen with a product that is illegal under international law, and which cannot be exported or imported legally.

On the black market, hash producers are paid poorly compared to the profits that can be generated by the middlemen, wholesalers, and retailers. However, there are one or two reports of something that could almost be termed “Fair Trade” occurring on the illicit market.

In 2015, VICE reported on a group of vendors known as The Scurvy Crew that sell products on the deep web illicit marketplace, The Silk Road, which closed in 2013. The Scurvy Crew set up exclusivity agreements with farmers that included a “sign-on bonus” intended to allow them to improve living conditions for themselves and their families. The crew’s ringleader Ace mentioned that many farms were “completely derelict”. In one instance, the crew paid for medical treatment for a farmer’s wife, as well as renovating his farm.

Is it possible to create a Fair Trade system for hash?

As long as international trade in cannabis and hash remains illegal, it is impossible to establish a true Fair Trade system to ensure improved distribution of profits. However, we may well see more relationships like those established by The Scurvy Crew, as there are great benefits to be derived for both producer and buyer in such systems. The VICE article notes, for example, that the crew’s ethics led to a “great working relationship” with producers, ensuring a steady flow of premium-quality hash to their customers.

On the other hand, it is important to consider the fact that if cannabis was to become truly legal, the price it would command on the open market would be likely to decrease substantially over time, until it compared to other legal cash crops such as grapes (a good comparison, as grapes are also used to make a highly-taxed product that causes intoxication, and thus command a high price per hectare compared to other legal crops).

Per hectare, illegal crops are more valuable by far than legal crops, precisely due to the fact that they are illegal. Cultivation, processing and distribution come with higher risks for illegal crops, and therefore demand greater value.

According to UN data, cannabis is worth almost $48 million per square kilometre. Just for comparison, grapes are worth about $625,000 per km², while tomatoes are worth $1.415 million. Grapes and tomatoes are among the most lucrative crops in the world, and cannabis is worth exponentially more. If cannabis were to drop to such comparatively low values per km², even the fairest Fair Trade system in existence may not be comparable to the revenues earned while it remains illegal.

What makes this issue particularly complicated is that while legalization is spreading in the USA, Canada, Europe and even Australia, this change isn’t transferring to the biggest manufacturers of hash: India, Afghanistan and Morocco. Even if retailers or importers in the USA or Europe wish to participate in fair trade dealings, it is extremely hard to orchestrate if cannabis is illegal in the place of origin.

Is there a case for fair trade cannabis?

The case for fair trade cannabis isn’t nearly as strong as that for hashish. This is because in general, very little cannabis is transported internationally because in countries where it is legal, there is a local growing program. In countries where it is illegal, it is either used to manufacture hash (which may then be exported) or it is sold locally on the black market.

The only large-scale cannabis import/export that has taken place in recent decades is hemp. Before the 2018 Farm Bill, it was illegal to cultivate hemp in the USA. Therefore, most of it was imported from Europe. Because most European countries are developed, there is less likelihood for exploitation of farmers.

At the root of it, fair trade cannot really happen without free trade. Both parties must be free to set the terms of the agreement, as this is what constitutes the fairest trade. With that being said, it is a circumstance nearly impossible to create in a global climate where cannabis is illegal. The illegality itself creates opportunities for exploitation, and the perfect environment for a superiority-inferiority complex between farmers and retailers.

The Dutch government advisory commission has addressed this issue before. The Dutch government is generally eager to support fair trade, even in the country’s cannabis dealings. While they acknowledged the problem, they also reported that they ‘could not discuss possible imports of cannabis from abroad, given the international legal obstacles to the production and distribution of cannabis at an international and EU level.’

Should legalization become widespread around the world, it would be imperative to impose structures to ensure that the developing world is given an equal chance to participate in the industry. This is not just for the potential to make money, but also for the possibility to ameliorate public health and living conditions by making hemp and medical cannabis accessible once more.

- Disclaimer:While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this article, it is not intended to provide legal advice, as individual situations will differ and should be discussed with an expert and/or lawyer.

I grew up in the late sixties and with the long hair and clothing would be classed as a hippie and all we had was good hash and very rarely saw grass I would love to go back to the days of hash the modern green you buy today is not a match for the old hash days I can under stand why people even of my age risk growing there own

Thank you for this thoughtful & informative article. Here in Scotland people would like to buy any hash if there was some or they have to make it themselves. Oh for Afghani black over here – those were the days.

I for one would love to see the return of an imported hashish market, with so much emphasis on new hybrids and concentrates these days i cant help but feel saddened that whole generations will not experience the joys of artisan hashish. Made using traditions and techniques handed down over generations.

Great article.

Thanks

I was fortunate enough to have experience this incredible stuffin the 70’s, Lebanese Gold!!!!!!!

What’s up everyone, it’s my first pay a visit at this web page, and paragraph

is in fact fruitful in support of me, keep up posting these types of content.

More Afghan families turn to cannabis cultivation

"The cannabis price rise has developed in parallel with the opium price hike caused by the opium crop failure in 2010, making its per-hectare income similar to that of opium and thus financially very attractive to farmers," the UN report said.

"But because cannabis cultivation is less labour intensive – less weeding is involved and the extraction of 'garda' (powdered cannabis resin) can be done at home in a matter of weeks with the help of family members instead of hired labour – it is actually more cost-effective than opium."

Surely growing cannabis instead of opium should be encouraged?

The roots of Fair Trade began in Europe after World War II as a faith-based initiative to help provide livelihoods for eastern European war refugees. Non-profits, such as Oxfam, with an interest in alleviating global poverty, worked to create markets for the refugees’ products. In these early days, “fair trade” followed a charity, or solidarity, model where the disadvantaged received market assistance.

great idea,lets all stick 2gether on this,

The solution to prohibition is as simple as three words:

1) DEschedule.

2) Repeal.

3) DONE!

Once it's over, the underground market will never be able to compete with either the legitimate retail market, nor will they have as many customers, since many people will opt to grow a few plants for themselves.

It's time to end this idiocy once and for all…

I would seriously get involved in that, people all over morocco, afghanistan, India and Mexicco pump out metric tons each year and depend on it as a cash crop as a farmer would his crop and livestock. The profit inevitably is dissolved in a myriad of levels of selling in smaller and smaller quantities for an increasing rate until it is finally appreciated. Just like Cocoa and Coffee growers, credit must go to the endemic growing communities upholding centuries of tradition.

Make this serious. Lobby government authorities with a well formed end plan. Approach medical authorities, approach the massive pool of celebrities that have already endorsed marijuana usage, approach the increasingly aware young generation that appreciates the marijuana culture.

This is something that can increase 'dope's' integrity.

love the fair trade article how can i help

great article i think fair trade hash is the best idea

Here in Denmark you support motorcycle-gangsters, who also do traffic with women, slaves and all kind of serious crime.Those sociopaths,among other violent motherfuckers with 9mm guns in their trousers earn a lot of money when you buy shit-soapbar "hash"! DONT BUY THAT SHIT! Grow your own!

Thats make perfect since to me,why support terrorism, what do politicians and gangsters have in common they don`t want peace they want scared people they can control,weed is not as bad as acholol or hard drugs wealthy people control the world,I`d meet the almighty lord with a joint in my hand and not be ashamed it bullshit that weeds illegal!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!