Malaria is a parasitic, mosquito-borne disease that affects more than 200 million people worldwide. It can be fatal, though not all strains are equally lethal. Cannabis, or cannabinoids more specifically, may hold the power to prevent devastating effects of some forms of malaria, particularly cerebral malaria, and even increase lifespan expectancy.

There are five Plasmodium species that can cause illness in humans:

- P. falciparum & P. vivax: These are the two primarily responsible for malaria deaths in humans

- P. ovale & P. malariae: These two cause a milder, generally non-fatal form of malaria

- P. knowlesi: This one causes malaria in macaque monkeys, and can be transmitted to humans with severe, but usually non-fatal results.

Malaria is transmitted by around one hundred separate species of mosquitoes, although there are thirty to forty species that are more commonly known to do so. All species of mosquito that transmit malaria belong to the Anopheles genus and are female; A. gambiae is particularly known as a malaria vector.

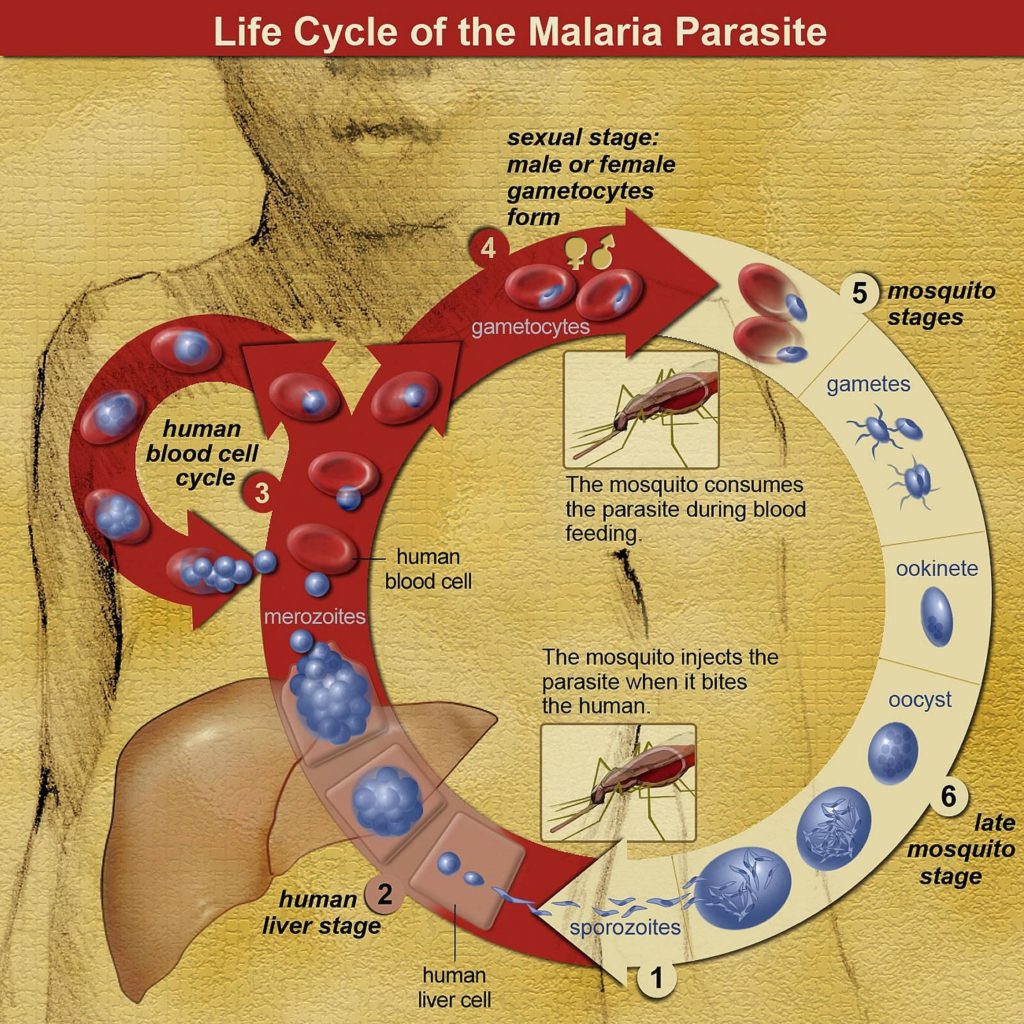

Life cycle of malaria

The life cycles of the above-mentioned Plasmodium species depend on the presence of both a human (or mammal) and a mosquito host and happens in three stages:

- Mosquito stage (sporogenic cycle)

- Human liver stage (exo-erythrocytic cycle)

- Human blood stage (erythrocytic cycle)

When a mosquito bites an infected human, it ingests haploid Plasmodium gametocytes (immature male and female reproductive cells). These then develop into mature male and female gametes, which fuse together to form diploid zygotes.

The zygotes then develop into actively-moving ookinetes, which burrow into the intestinal walls of the mosquito. Here, the ookinetes develop further into oocysts—thick-walled cellular structures that manufacture small haploid cells known as sporozoites.

After 8-15 days, the oocysts burst and release a flood of sporozoites, which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. The next time the mosquito bites a human, it will then release the sporozoites into the bloodstream of the human host. Once this occurs, the sporozoites infiltrate the liver cells and begin to grow and divide, forming new haploid cells known as merozoites.

How does malaria affect humans?

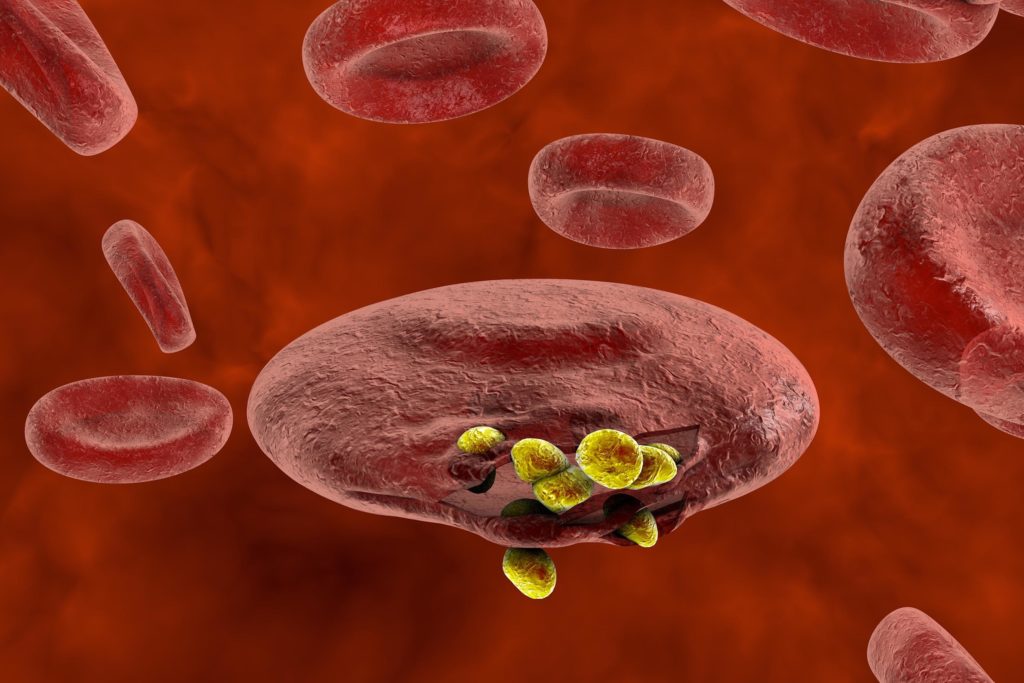

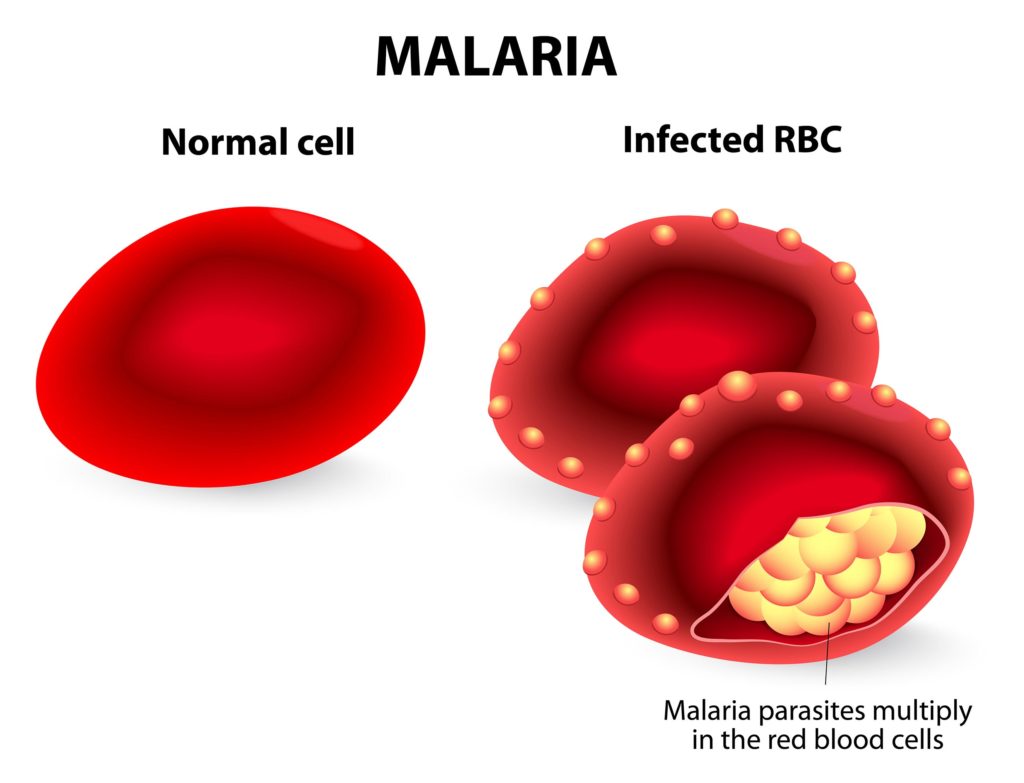

The merozoites continue to reproduce asexually, producing tens of thousands of offspring, and ultimately cause the liver cells to burst. The merozoites then exit the liver, rejoin the bloodstream, infiltrate the red blood cells, and continue to reproduce and divide.

Some merozoites don’t reproduce asexually, and instead form male and female gametocytes. Thus, the infected human will pass on the gametocytes to the next mosquito that ingests its blood, thereby completing the cycle.

Malaria becomes symptomatic when the merozoites have multiplied sufficiently to affect multiple cells in the bloodstream—this usually occurs within two weeks of infection, although dormant periods of several months or years can occur with some Plasmodium species.

As the merozoites multiply within the red blood cells, they periodically cause them to burst, whereupon the merozoites escape back into the bloodstream and infect new red blood cells. These burst-and-infiltrate cycles occur periodically, and correspond with the cyclical recurrence of fever in infected individuals.

In cases of infection by P. falciparum, infected red blood cells can breach the blood-brain barrier before bursting, which can lead to cerebral malaria.

Symptoms of malaria

Symptoms of malaria usually manifest within 15 days of the infecting bite. The five malaria species cause similar initial symptoms, with headache, fever, joint pain, vomiting and shivering most commonly observed. Convulsions, jaundice, anaemia and damage to the retinas are also common early symptoms.

Malaria is often characterised by cyclical recurrent fever, or paroxysm, which corresponds with the cycle of bursting and infiltration of the red blood cells. Depending on the species of Plasmodium that has infected the host, the duration of the fever cycle varies.

With P. vivax and P.ovale, fever typically recurs every two days, while with P. malariae the cycle lasts three days. In P. knowlesi, the fever recurs on a 24-hour cycle, while P. falciparum may cause recurrent fever every 36-48 hours, or may cause a milder but continuous fever.

Prognosis of malarial infections

When treated early, malaria patients often successfully beat the illness and regain full health. It’s estimated that in 2017, around 435,000 deaths occurred as a result of around 219 million malaria cases. The mortality rate seems to have dropped some from 2012, when there were 627,000 deaths among 207 million cases.

However, malaria cases are often poorly documented, and some state the annual prevalence to be much higher—up to 500 million cases per year.

However, if treatment does not occur immediately on onset of symptoms, the disease can progress in severity extremely rapidly, and can cause death in a matter of days. Death usually occurs as a result of complications such as acute respiratory distress, which can occur due to acute anaemia, pulmonary oedema (accumulation of fluid in the lungs) or pneumonia.

Complications & mortality

Blackwater fever is another complication of malaria. This occurs due to the rupturing of red blood cells in the bloodstream, which allows the release of haemoglobin directly into the blood and urine. This can lead to renal failure, which is typically fatal if untreated. The complication is characterised by the presence of dark-red or black urine.

Cerebral malaria has a higher mortality rate than simple malaria, causing most malaria-related deaths globally. Not all cases of P.falciparum result in breaching of the blood-brain barrier to cause cerebral malaria, and instances of it occurring are far more common in children below the age of five.

Although its prevalence is low, it’s one of the more severe complications of P. falciparum. As of 2010, it was reported to affect around 575,000 children alone each year. Cerebral malaria may often lead to coma, permanent neurological difficulties, and possibly death.

History of treating malaria with cannabis

Cannabis has a long history of use against diseases that cause symptoms of fever, such as cholera, rabies and tetanus. There are documented instances of use by ancient cultures including those of China and India; anthropologists have also documented traditional use which persists to this day among some African and Southeast Asian populations.

The early Chinese literature makes reference to cannabis being used as a treatment for malaria. Summarising its therapeutic properties, the Pen T’sao Ching states that cannabis ‘clears blood and cools temperature’, a reference to cannabis’ ability to reduce fever.

In Cambodia, people infected with malaria were traditionally treated with cannabis; such use may persist to this day in some regions. Reportedly, the smoke from one kilogram of male and female plants is inhaled twice daily until the fever has passed. Occasionally, an alternative method is employed, whereby a preparation of cannabis and water is administered orally in two-millilitre doses prior to each meal. However, this method is held to be less effective.

In Africa, cannabis is reported to have been used by Zimbabwean traditional healers as a remedy for malaria, as well as for blackwater fever, a potentially-fatal complication of the disease. It’s believed that traditional cannabis-based medicines continue to be in use among rural populations both in Africa and in Southeast Asia.

Use in traditional Indian medicine

In 1893-1894, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report referred to cannabis being used as a prophylaxis against malaria, administered in the form of ‘a cool refreshing drink’. At the time, cannabis was widely used in both the Ayurvedic (Hindu) and Tibbi (Islamic) branches of medicine as a hypnotic, analgesic and antispasmodic. The diaphoretic (perspiration-inducing) and diuretic properties of cannabis were considered effective in reducing fever.

In 1957, Indian doctors I. C. Chopra and R. N. Chopra published an in-depth report on the uses of cannabis in traditional Indian medicine. According to the report, cannabis was in common use ‘as a smoke and as a drink’ in malarial regions, where it was believed to be effective as a prophylactic.

The submontane and Terai (savannah and grassland areas of northern India and Nepal) regions of Uttar Pradesh state, where wild cannabis is abundant, are specifically noted for their extensive use of bhang (a cannabis-based drink)as a treatment for malaria.

Bhang is believed to be more effective than ganja (herbal cannabis) in allaying the ‘general feeling of restlessness’ brought on by malarial fever. For medicinal purposes, it appears that cannabis was more commonly administered orally, and rarely by smoking. However, in some regions, hashish (colloquially known as nasha or charas) was smoked to both treat and prevent malarial headache.

The decline of traditional cannabis treatments for malaria

By the end of the 19th century, cannabis and hashish-based medications were in widespread use in the USA and Europe. Such treatments were in use for malaria, but their application for this purpose was apparently limited compared to their use in other areas of medicine. Of course, prohibition of cannabis dealt a fatal blow to its use in medicine, at least in the Western world.

The UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) was strongly protested by India and other sympathetic nations. In recognition of cannabis’ cultural significance, India was given 25 years to enact specific legislation. Despite this, the Chopra & Chopra report of 1957 stated that use of cannabis in Indian folk medicine had already begun to rapidly decline in the preceding decades.

One factor was the decline in potency and consistency of cannabis-based medicines—as the global market for Indian hemp declined, so did the domestic industry. Furthermore, the number of potent and effective modern drugs available on the market had sharply increased, and had begun to replace traditional cannabis treatments.

However, at the time of the report it was observed that practitioners of indigenous medicine still made extensive use of cannabis in the rural areas of India, and that cannabis-based preparations remained popular household remedies for many minor ailments. Roving mendicants, still common throughout India, often carry and use bhang, and may still on occasion supply it to villagers in rural locations.

Modern research into cannabis & malaria

While modern research into cannabis as a treatment for malaria is sparse, one or two studies do exist. A study published in 2007 compared the effectiveness of extracts taken from cannabis and another plant widely used in folk medicine, Aloe vera (also known as A. barbadensis), in killing larvae of the vector mosquito species Anopheles stephensi. While not directly treating malaria itself, such tactics can represent an important step in preventing transmission of malaria.

Individual plant specimens of both species were treated with three different solvents—carbon tetrachloride, petroleum ether and methanol—to produce three different extracts. The study demonstrated that both cannabis and aloe vera extracts showed effectiveness in killing the larvae, with the carbon tetrachloride extracts being significantly more effective. However, all extracts taken from Aloe vera were shown to be more effective than those taken from cannabis.

CBD may prevent damage from cerebral malaria

Cerebral malaria is a severe and potentially devastating complication of P. falciparum infection, which can cause permanent neurological and behavioural deficits, even after infection resolution by antimalarial drugs. Cannabidiol (CBD), the major non-psychoactive cannabinoid found in C. sativa, has been repeatedly demonstrated to potentially exert a neuroprotective effect in some illnesses. It has also been shown to slow the rate of neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease.

A study published in 2015 aimed to investigate whether CBD could prevent behavioural changes in mice infected with P. berghei-ANKA. This species of Plasmodium doesn’t affect humans, but will cause symptoms in many mammal species, and is a widely-used model organism for research purposes. Commencing three days subsequent to infection, some mice were injected with 30mg/kg doses of CBD.

Five days subsequent to infection, the infected mice were treated with artesunate, an established malaria treatment that works by reducing parasitemia (parasite load in the blood). After artesunate treatment and full reduction of parasitemia, the mice were subjected to memory and cognitive tasks.

Mice that were solely administered with P. berghei-ANKA displayed memory deficits and increased anxiety, whereas mice treated with CBD did not display these effects.

Although not replicated in humans, these results indicate that CBD could prove useful as an adjunctive therapy to reduce or entirely prevent brain damage caused by cerebral malaria.

Difficulties in treating malaria

The available treatment options for malaria are limited. Plasmodium parasites, including P. falciparum, are becoming more resistant to the most common class of anti-malarial compounds, the artemisinin group, of which artesunate is a member.

Overuse of synthetic chemicals such as DDT has encouraged mosquito populations to develop resistance (Tonnendreher).

As methods of killing the parasites directly are few and decreasingly reliable, the focus has shifted onto the use of synthetic pesticides to control the populations of the disease vectors— Anopheles mosquitoes. This has led to abundant use of synthetic pesticides, including one of the most notorious—dichlorodiphenyl trichloroethane (DDT).

Due to this overuse, vector mosquito species are becoming more resistant to synthetic insecticides such as DDT, and populations that were previously under control are increasing again in some locations.

Despite this, continued application of these dangerous synthetic chemicals is causing serious and widespread environmental damage, including the destruction of non-target species, bioaccumulation, and loss of biodiversity.

As a result of these alarming developments, there is increased need for alternative treatment methods for malaria that don’t cause widespread environmental damage—and to which vector mosquitoes or Plasmodium species have not developed resistance.

Is cannabis still useful as a treatment for malaria?

Due to improved modern methods for treating malaria, as well as its current illegal status, the use of cannabis as a remedy for malaria has fallen by the wayside. However, given that malaria remains a significant risk for almost one half of the world’s population, particularly in developing countries, any drug that can be produced locally and at low cost is worth considering as part of the array of available treatment methods.

While treatments may have improved, prevalence remains extremely high, largely due to the poverty of affected nations and the logistical difficulties inherent in distributing the necessary drugs.

Furthermore, cannabis is indigenous or naturalised in almost every region of the world—particularly in and around the tropics—where malaria is endemic. If made legal and regulated, it could still be usefully implemented as a prophylactic and fever reducer. There are other plants that may be more effective than cannabis at treating specific malaria symptoms, such as Aloe vera, but they don’t generally have the breadth of application in medicine that cannabis offers.

By far, the most exciting discovery is the potential for cannabidiol to lessen the neurological damage caused by cerebral malaria. This potentially life-altering complication of P. falciparum infection affects over half a million children every year, and even when not fatal can have consequences that negatively affect the sufferer throughout the course of their life. Low-cost cannabidiol treatments could have a very significant part to play in reducing the prevalence of this phenomenon.

- Disclaimer:This article is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with your doctor or other licensed medical professional. Do not delay seeking medical advice or disregard medical advice due to something you have read on this website.

Beautiful article. I’m still skeptical about using cannabis for malaria, especially when on antimalarial drugs. I don’t know if the cannabinoids will affect the bioavailability of the drug positively or negatively. ??

Man, last 2 weeks ago, Malaria almost killed me. I couldn’t eat, throwing up anytime I try to eat. Taking drugs was difficult for me, I felt like dying.

So one day I decided to smoke weed(loud) cus I quit smoking while taking my drugs.

The day I resumed smoking, I started eating too much, my headache reduced and I felt like it wasn’t sick.

I swear to God, I felt better til today.

So anytime I have this crazy symptoms, I just run to smoking weed.

I use it when I visited Africa it really work

Also consider that freshly Made Carrot Soup are recommended home remedies for typhoid fever.

I was cured from Malaria in Africa with Cannabis.

I have 2 types of Malaria Falciparum and Vivax.

The fevers and sweats are very intense and I use sweet wormwood and cloves which help considerably.

I also have Bio Resonance treatment.

I am also going to try CBD oil with a 16.5% of CBD to help with the joint pains and fever along with Aloe Vera pure juice. after reading this article.

Maybe this will work better?

Thanks for the research.

Much appreciated and I will let you know of any further improvements.

Paul.

Yes cannabis worked for me in Africa. Lots of fluids as well. If you smoke cannabis the mosquitoes will also stay away!

very useful article. i tried many plant extract for larval control

kindly send me more

Beautiful write up. I’ll love to know more.