Sometimes languages use the scientific name as the common name, such as the British use of the word “cannabis” to denote Cannabis drugs. Modern-day marijuana users commonly describe hybrid Cannabis varieties as being “more indica” or “more sativa” which are terms casually derived from valid scientific names. Where did these terms come from? How did they become associated with different varieties of drug Cannabis?

Common names for plants and animals are often of very local usage and may mean nothing, or something entirely different, to speakers of another language. Scientific names, derived at least in part from ancient Greek and Latin, were created so someone interested in a certain organism, researching in their own or a foreign language, can know exactly whether others are referring to that same organism. Sometimes languages use the scientific name as the common name, such as the British use of the word “cannabis” to denote Cannabis drugs. Modern-day marijuana users commonly describe hybrid Cannabis varieties as being “more indica” or “more sativa” which are terms casually derived from valid scientific names. By so doing they usually mean that a variety produces either more corporeal effects on the body or more cerebral effects on the brain. Generally, “indicas” are better suited for relaxing on the couch, while “sativas” are more enjoyable for more mental activities such as gaming, writing or playing music. Where did these terms come from? How did they become associated with different varieties of drug Cannabis? Can a deeper understanding of Cannabis’s names give us insights into its complex evolution and enhance our appreciation of the profound diversity experienced in drug Cannabis today?

Origins of Cannabis sativa

The scientific name Cannabis sativa was first published in 1753 by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus who is known today as the father of modern taxonomy, the science of classifying organisms. The term sativa simply means “cultivated” and describes the common hemp plant grown widely across Europe in his time. C. sativa is native to Europe and western Eurasia where it has been grown for millennia as a fiber and seed crop, and was introduced to the New World during European colonization. In short, we wear C. sativa fibers and we eat C. sativa seeds and seed oil, but we do not smoke C. sativa plants as they have little ability to produce the cannabinoid delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or THC, the primary psychoactive and medically valuable compound found in Cannabis. In addition, compared to the essential oil of C. indica varieties, C. sativa produces less quantity and variety of terpenes, which are increasingly shown to be of importance in the efficacy of Cannabis medicines. C. sativa represents a very small portion of the genetic diversity seen in Cannabis worldwide, and it is not divided into subspecies based on differing origins and uses like C. indica. Linnaeus likely had never even seen any drug Cannabis, and it is incorrect to use “sativa” to describe drug varieties.

Origins of Cannabis indica

More than 30 years later, in 1785, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck described and named a second species, Cannabis indica, meaning the Cannabis from India where the first samples of the plant reaching Europe originated. C. indica is native to eastern Eurasia and was spread by humans around the world primarily as a source of psychoactive THC. C. indica is used for marijuana and hashish production, but in many regions of eastern Asia it has a long history of cultivation for its strong fibers and nutritious seeds. In short, we wear C. indica fibers, and we eat C. indica seeds and seed oil, but we also use C. indica as a valuable recreational and medicinal plant. C. indica includes the vast majority of Cannabis varieties living today and is divided into several subspecies with differing origins and uses.

The Cannabis debate

Since the 1960s taxonomists have championed several different naming systems. Many preferred a three species concept by recognizing C. ruderalis as a wild species possibly ancestral to both C. sativa and C. indica. Others chose to reduce C. indica and C. ruderalis to subspecies or varieties of a single species C. sativa. In the late 1970s markedly different appearing hashish varieties were introduced to the West from Afghanistan and considered by some to be the true C. indica and by others as a fourth species C. afghanica, while all the other drug varieties were held to be members of C. sativa following the single species model. By the dawn of the new millennium confusion and disagreement reigned, but better science would prevail.

Reconciliation through taxonomic groupings

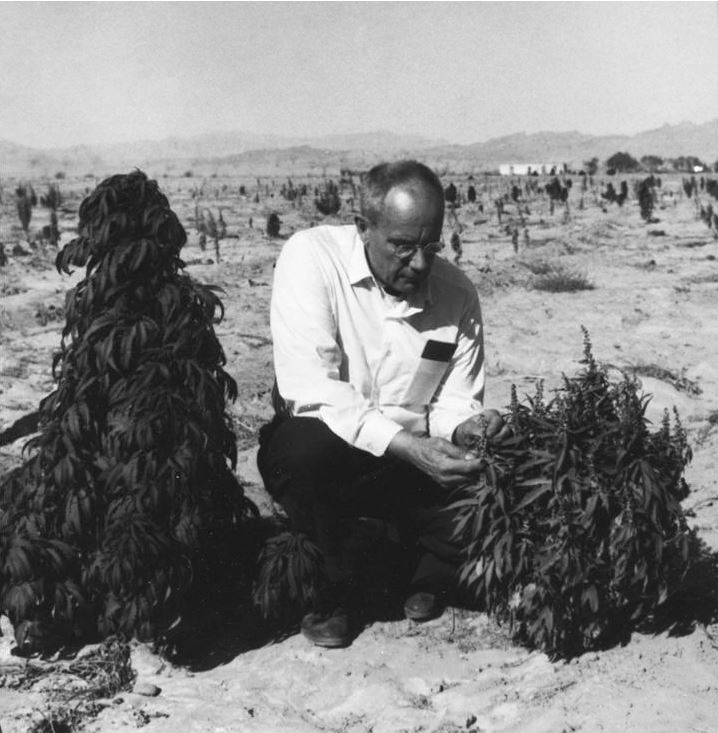

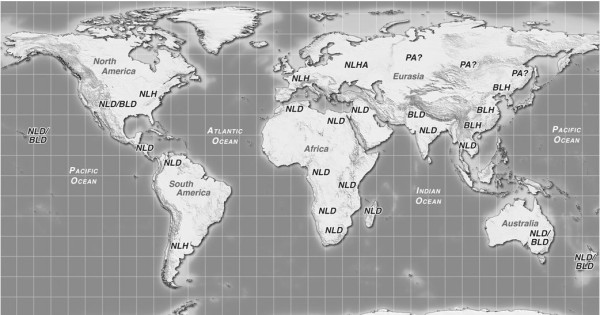

Karl Hillig at Indiana University (published 2004, 2005) investigated the diversity of Cannabis by characterizing the chemical contents of plants from a wide range of geographical origins and usages; and he proposed taxonomic groupings (subspecies) that both reconciled the previous naming systems, and fit well into a hypothetical model for the evolution of Cannabis. Hillig’s research supports the original two-species concept for Cannabis—C. sativa Linnaeus and C. indica Lamarck—with C. indica being far more genetically diverse than C. sativa. Hillig recognized the European cultivated subspecies as C. sativa ssp. sativa. Because it typically has narrow leaflets and is used for hemp fiber and seed production, he named it narrow-leaf hemp or NLH. He also identified spontaneously growing wild or feral populations previously called C. ruderalis as C. sativa ssp. spontanea which he named the putative ancestor or PA and I refer to as the narrow-leaf hemp ancestor or NLHA.

Four C. indica sub-species

Hillig grouped C. indica varieties into four subspecies—three based on their diverse morphological and biochemical traits, and another characterized largely by its spontaneous growth habit.

Subspecies indica

indica ssp. indica varieties range across the Indian subcontinent from Southeast Asia to western India and into Africa. This is what Lamarck described as C. indica or Indian Cannabis. Subspecies indica populations are characterized as having a high content of THC with little if any cannabidiol or CBD—the second most common cannabinoid, which is non-psychoactive, and has also been shown to have medical efficacy. By the 19th century these drug varieties reached the Caribbean region of the New World, steadily spread throughout Central and South America, and since the 1960s have been exported to Europe, North America and beyond forming the early sin semilla marijuana gene pool. Marijuana users commonly call them “sativas” because their leaflets are relatively narrow, especially in relation to the Afghan varieties or “indicas” that were introduced later, and therefore exhibit a superficial resemblance to European C. sativa narrow-leaf hemp or NLH plants. However, this is a misnomer as C. sativa plants produce little if any THC. Based on Hillig’s research we now call members of C. indica ssp. indica narrow-leaf drug or NLD varieties, because although they also have narrow leaflets, they produce THC and are therefore drug varieties.

Subspecies afghanica

Subspecies afghanica originated in Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan, where crops were traditionally grown to manufacture sieved hashish. From 1974, when Afghan Cannabis was first described in English by Harvard professor Richard Schultes, it became readily apparent that it represented a type of drug Cannabis previously unknown to Westerners. Its short robust stature and broad, dark-green leaves distinguished it from the taller, lighter green and more laxly branched NLD varieties. By the late 1970s seeds of Afghan hashish varieties reached Europe and North America and were rapidly disseminated among marijuana growers. At this time all Cannabis varieties were commonly considered to be members of C. sativa, and the familiar NLD marijuana varieties were called “sativas” to differentiate them from the newly introduced and quite different looking varieties called “indicas.” Hillig named the Afghan hashish varieties C. indica ssp. afghanica and I call them broad-leaf drug or BLD varieties to differentiate them from NLD varieties. BLD populations can have CBD levels equal to those of THC. Both subspecies indica and subspecies afghanica produce a wide array of aromatic compounds that are important in determining their physical and mental effects.

Subspecies chinensis

Hillig’s third grouping within C. indica is subspecies chinensis which comprises the traditional East Asian fiber and seed cultivars which we call broad-leaf hemp or BLH. Like other subspecies of C. indica, chinensis varieties possess the genetic potential to produce psychoactive THC, but East Asian cultural constraints encouraged the selection of these varieties for their economically valuable fiber and seed rather than their psychoactive potential. Asian and European cultures have many similar uses for hemp fiber and seed.

Subspecies kafiristanica

The fourth subspecies C. indica ssp. kafiristanica includes spontaneously growing feral or wild populations, and Hillig hypothesized that it might be the narrow-leaf drug ancestor or NLDA.

The ruderalis debate

Some researchers have also suggested a third species C. ruderalis as the progenitor of both C. sativa and C. indica. Evolutionary theory predicts that there must once have been a common ruderalis-like ancestor of the two modern species, but it has most likely become extinct, and proposed groupings NLHA and NLDA represent feral populations of NLH and NLD respectively rather than ancestors. C. sativa NLH likely originated in a temperate region of western Eurasia—possibly in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains—from a putative hemp ancestor or PHA which lacked the biosynthetic potential to produce THC. C. indica likely originated in the Hengduan Mountain range—in present-day southwestern China—from a putative drug ancestor or PDA which had evolved the ability to make THC. This PDA would then have diversified as it was spread by humans to different geographical regions where it further evolved into NLD, BLD and BLH subspecies, all of which make THC and complex suites of aromatic terpenes. These subspecies of C. indica are the source of all psychoactive Cannabis found today. So, when we talk about psychoactive Cannabis we mean C. indica as there are no drug “sativa” varieties. What people commonly refer to as “sativas” are really C. indica ssp. indica and for convenience should be called narrow-leaf drug or NLD varieties. And, what are commonly referred to as “indicas” truly are C. indica ssp. afghanica broad-leaf drug or simply BLD varieties.

Heirloom landrace cultivars

Cultivated crop plant varieties are called cultivars, and when cultivars are grown and maintained by local farmers we refer to them as landrace cultivars or landraces. Landraces evolve in a balance between natural selective pressures exerted by the local environment—favoring survival—and human selections favoring a cultivar’s ability to both thrive under cultivation and to produce particular culturally preferred end products. Early humans spread Cannabis as they migrated, and at each new location selected seed from superior plants within these early populations, those appropriate for their own individual uses and processing methods. By sowing seeds from the most favorable individuals, traditional farmers developed and maintained the high-quality landraces upon which the home-grown marijuana industry was founded.

Traditional sinsemilla landraces from faraway Asian countries like India, Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam; African landraces from South Africa, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and more; as well as New World landraces from Colombia, Panama, Jamaica, and Mexico are all NLD varieties. Hybrids between imported NLD landrace varieties formed the core genome of domestically produced marijuana in both North America and Europe before the introduction of BLD landraces from Afghanistan in the late 1970s.

Cannabis Today

Presently, almost all modern drug Cannabis varieties are hybrids between members of two C. indica subspecies: subspecies indica, representing the traditional and geographically widespread NLD landrace marijuana varieties, and subspecies afghanica, representing the geographically limited BLD hashish landraces of Afghanistan. It is through combining landraces from such geographically isolated and genetically diverse populations that the great variety of modern-day hybrid recreational and medical Cannabis varieties blossomed.

Unfortunately, we cannot return today to a region previously known for its fine Cannabis and expect to find the same landraces that were growing there decades before. Cannabis is open-pollinated, with male and female flowers borne on separate plants, and therefore to produce a seed usually two plants must be involved. Random combinations of alleles and accompanying variation are to be expected. Cannabis landrace varieties are a work in progress. They are maintained by repeated natural and human selection in situ—nature selecting for survival and humans selecting for beneficial traits—and without persistent human selection and maintenance they drift back to their atavistic, naturally selected survival level.

Preserving the legacy

The western world turned on to imported marijuana and hashish in the 1960s and all the amazing imported varieties available then were traditionally maintained landraces. Within a decade the demand for quality drug Cannabis exceeded traditional supplies, and mass production in the absence of selection became the rule. Rather than planting only select seeds, farmers began to sow all their seeds in an effort to supply market demand, and the quality of commercially available drug Cannabis began to fall. This decline in quality was exacerbated by pressure on Cannabis production and use from law enforcement branches of most governments worldwide. Landraces can no longer be replaced, they can only be preserved. The few remaining pure landrace varieties in existence now, kept alive since the 70s and 80s, are the keys to future developments in drug Cannabis breeding and evolution. It will be a continuing shame to lose the best results of hundreds of years of selection by local farmers. After all, our role should be as caretakers preserving the legacy of traditional farmers for future generations.

NOTE: For more in-depth discussions of Cannabis taxonomy and evolution please explore my recent book written with distinguished professor Mark Merlin from the University of Hawai’i called Cannabis: Evolution and ethnobotany published by University of California Press and available here.

Lamarck never saw a living Indic Plant. Botaniists dont discuss about that.

Why you do?

And so there are possible mistakes.

Why you can cross those “species” up to Fxx without getting them steril?!

Would you call chinese people-arabian-etc as own specia or subspecia`?

Why the KZG – at Indica and Sat is among 14,5 hours-

and why ruderalis plant dont have that:

because it is

Cannabis sat. subssp. sat/ind/rud —-

and indeed you can make subspecies for that 3 kategories.

The most important thing ist- is it poyid or haploid.

Do you have more ressoureces for that debate?

Kindly

I have a question tho, how was that the Indica and Sativa names of today´s seed banks and common place magazines got this way of calling them? i mean, i understand that when the BLD entered occidental world some people thought they were facing the real indica. something that was wrong, because NLD was the one that came from India, Lamarck was right in the first place. but how it perpassed academy and reached recreational markets? how it got the strenght of today, since it had to be changed from that one that came from 200 years ago? wasnt it easier in the first place, in the 70`s, just add another taxon for that new finding, instead of shaking the whole picture? thanks for the att.

great article, thanks for sharing the knowladge.